HELLO.

I change my blog only slightly less frequently than I change my job.

For future Quinns blogging, please travel here.

this reality is better

HELLO.

I change my blog only slightly less frequently than I change my job.

For future Quinns blogging, please travel here.

(Images courtesy of BoardGameGeek.com)

Why should you, a video gamer, take up board gaming?

We’ve arrived at the finale. It is a slightly wet finale, but I’m going to try and dribble that moisture upside your head in a kind of literary waterboarding.

In part 1 I talked about how board games represent lossless game design. In part 2 I just listed a set of mad, brilliant board games that you probably never knew existed. I promised, though, that in part 3 I’d give you the “real” reason you should be buying these things and conscripting your friends into coming over.

So: Videogame multiplayer used to centre around single-screen, single-couch shenanigans. We still have it today- games still do offer us the chance to sit thigh to thigh with a buddy and gun and thrust our way through levels in split-screen. Of course they do. Because experiencing multiplayer with the other players sat right there is at the very least a little more tense (think large-scale LAN parties), and at best an absurdly elevated experience (think 4-player Bomberman). You feel more connected to the humans you’re playing with.

It’s a weird one, shown by the following thought experiment: Imagine playing Bomberman online when you’re alone at home. Now imagine playing it on a network in the same office as the other players, but you’re all in separate cubicles and aren’t allowed to speak. Now imagine you can speak, shouting over the walls. Now imagine you’re sat side by side, and can talk, but aren’t allowed to turn your heads to look at one another. And finally, imagine playing Bomberman on the sofa, shouting and laughing, without some weird imaginary fascist forcing you to play the game in odd ways to prove a point. Each step of the way, the experience becomes richer.

Said point is that despite the games industry’s hurried adoptance of online multiplayer, play has a deeply social component. Sure, the ubiquity of high-speed internet connections has set designers free, in a sense. Friends lists and headsets mean we can play with whoever we want, wherever they are. MMOs let us shank rats as one hero among thousands. Most recently, Journey and Demon’s Souls turned the anonymity of online multiplayer to their advantage.

All the same, online videogames are starting to leave behind something that’s important to the human experience. Here, Scottish comedian Rab Florence says it better than I ever could.

I had Subbuteo back in the day. We all did. American readers might not be aware of it. It was a tabletop football game where you flicked the players at a plastic ball, in an attempt to score goals. A football match, in plastic. I didn’t have a table large enough to take the large green sheet that served as the game’s pitch, so I would lay it out on the living room floor behind my da’s chair. Night after night, my da would play Subbuteo with the 10 year old me – I’d be Glasgow Celtic and he’d be Aberdeen, purely because the other team was a red colour.

Neither of us really knew the proper rules, and we were both terrible at the game. The matches were usually ghastly 0-0 grinds, because the playing surface was so poor. Folds and creases everywhere and lumps and bumps where the patterned carpet under the pitch undulated. A wee boy and his da, on their knees, flicking plastic men while Strike it Lucky blasted from the living room telly. My ma at the bingo. My whole life ahead of me. My da still alive.

I don’t know if Subbuteo is a great game. I’m sure it is. It just wasn’t really a game to me. It was just one of many things I shared with my da. Like Star Trek and in-depth conversations about the nature of the universe. Now, as a father myself, I realise what was actually happening when we were playing that game we didn’t know the rules of. We were just being with each other. Flicking plastic. Shooting the shit. Playing.

What’s the point of all this?

Being with each other – for me, that’s the key element of board gaming. When you get that occasional person who openly tells you they see board games as “sad”, I feel a bit sad that they don’t get it. If I want to play a board game with you, it really just means I want to sit with you a while. That’s not a bad thing, is it?

Here’s some more food for thought.

Once a year, the player pilots of the EVE Online universe literally take flight. They soar by the thousand towards Reykjavik for the annual EVE fanfest. I was there in 2011, and mostly the reasons why these people make the trip are the same as for any other internet meet. To put names to faces, sure, but mostly to get piss-drunk with good people who you can bond with immediately. Importantly, the EVE fanfest doesn’t augment the game itself. It’s an entirely separate entity, with a different appeal. Yet this appeal is strong enough that people will pay through the nose for it, for the flight, the ticket, the hotel room, the air-sucked-through-teeth price of Icelandic booze.

Basically, the convention centre that hosts Eve Fanfest is an enormous, ice-cold bubble of social lubricant.

This, I’ve realised, is the appeal of board games. Don’t compare them to video games, compare them to the socialising that happens around video games. Board games, unlike video games, are an excuse to meet, chat to, get drunk with, and have free, easy conversation with other humans. Except there’s also a fantastic game involved.

TL;DR: Board games are the nerdiest, most gamey excuse to sit down with people you care about, drink some beer and feel together. If that doesn’t sound like the best thing ever, I’ve got a scientifically proven theory. Either you’re not a gamer, or you’re not human.

But if you are a gamer, and you are human, and you’re sat there thinking, “Hey. Hey. Maybe it’d be pretty good to sit down with some of my closest friends, roll some dice and kill a bottle of Jack Daniels,” let me offer my heartfelt congratulations. Because you’re right. You’re so, so right.

So here’s what you do. You go to Amazon, or your local game shop if you want to do this Right. You buy a copy of Galaxy Trucker, Cyclades or Cosmic Encounter. You call up your friends, and you tell them you want them to come over play your new board game. That’s right, you said your new board game.

Tell them there’s a whole world of game design you’ve been neglecting. Then tell them there’s a whole aspect of gaming, a more social side, that’s been temporarily clouded and forgotten as we’ve started playing games online. Then tell them you love them. Then, while they’re reeling from that, tell them to bring booze.

Then hang up.

You tell me how it goes.

Right. At the end of part one of this essay on analog games, I said I’d talk about specific examples of board games to show why you, a video gamer, should be playing them.

“GO ON,” you shout, catapulting burrito filth from your mouth. “HOW GOOD COULD THESE GAMES POSSIBLY BE.”

Well, that’s not really the point. You’ll see. Let’s start with…

The Resistance.

You’re sat at a table. The lights are low. Around you are a half dozen of your friends, sipping from beer bottles and eyeing one another nervously.

More than half of you are legitimate members of The Resistance, seeking to undermine the government. The rest are double agents reporting back to that government. The “game” simulates the part of this story where you all meet to argue about which of you can be trusted to go on missions; which of you form the team that plants the bomb or kidnaps the official. The missions themselves are just the members of that team placing a card facedown, either sabotaging the mission or not. These cards are then shuffled and dealt face up, revealing the results of that mission.

You flip the cards… a pass, a pass, a pass and there it is- a sabotage card. At least one member of that team is a spy. But who? Cue frenzied accusations, nervous allegiances, and the leadership of your cell slipping clockwise around the group like a sweaty minute hand.

Which is a fancy way of saying The Resistance is just a game of talking.

Which is exactly why it’s important.

Never mind the fact that The Resistance is a beautiful game. Let’s glaze over the big things, like the fact that the spies know who one another are and must work together to sway suspicions away from their allies and towards the innocent, and also the little things like the rapid exchange of glances when two spies get sent on a mission together (which of them submits the sabotage card? they can’t both do it, or their spy ring will be rumbled).

The Resistance and games like it are important because video games cannot yet challenge our personal charisma, leadership and duplicity. They can’t challenge us socially. Hell, they’ve barely scratched the surface of bluffing. And to state the obvious, to ignore such a vast part of human existence is at best a crying shame.

We’re blindsided by what video games can do with such fierce regularity that we often forget what they can’t do. Like talking.

Or tactility! Which brings us to

Catacombs.

This game sees a team of heroes descending into a dungeon, and casts another player to control all the monsters. Are you asleep yet? Don’t be asleep.

The twist is that it’s a dexterity game. The heroes, monsters, arrows and fireballs are all wooden tokens. Want your barbarian to run the length of a room to hit a skeleton? You flick yourself at at that skeleton. If you hit, you kill it, if you miss, you miss. If the evil player wants his spider to envelop a hero in some sticky web, you flick a missile token from the spider to the hero. Want to hide behind cover? Flick yourself behind one of the game’s stone pillars, which socket into the board.

It’s World of Warcraft meets pool. Diablo meets beer pong. But the point is that you haven’t even heard of it. That’s the tradgedy here. This is a wonderful game, and there’s no reason why you, reading this, shouldn’t own it and play it with your friends on a weekly basis. But you haven’t even heard of it. No, it’s worse than that. You had no conception that something like this even existed. Doesn’t that make you a terrible gamer? It might do. I dunno.

Again: The popular conception is that boardgames are somehow primitive, but there is so much boardgames can do that video games can’t. Yet.

Are you starting to get it? Because I’m not even half way done giving examples.

Descent: The Road to Legend.

Descent is a more traditional hero team vs. evil player game. It’s a game of movement points and dice, in the style of Dungeons & Dragons. It’s pretty great. But the Road to Legend expansion is what makes it fascinating. Here’s her map:

What Road to Legend offers is grand campaign that the base Descent dungeon-crawling game sockets into. Essentially, in an ordinary game of Descent the heroes go slicing and bleeding their way through a dungeon, and that’s your evening’s enjoyment. In Road to Legend, those dungeons are all simple locations in a grand overworld full of cities, rivers and secret paths, and the hero party journeys around it as the evil player maneuveres powerful lieutenants to block them, besiege cities and bring about a dark plot.

To complete a Road to Legend campaign takes some 300 hours, taking a game that’s fun in and of itself, and growing a bigger game around it that has the scale and pace of The Lord of the Rings.

This is where things get a bit embarrassing for video games, because unlike the above two examples, video games could do this- something this mad and grand. But they haven’t.

Imagine if Blizzard announced a Starcraft II expansion that let players duke out grand campaigns, connecting 80 individual matches between 4 players into a space opera epic with its own map, its own rules. It would be exquisite. Different. Interesting.

Board games have been experimenting with this kind of scale, these sorts of campaigns, for decades, for the simple reason that they’re incredible fun. In the same way as persistent unlocks have revolutioned the last few generations of multiplayer FPS games, these cardboard campaigns let you take the hours you spend on an evening’s gaming and invest them into something bigger. Except instead of providing hollow, almost skinner box-like rewards, it weaves those games into a story with its own highs and lows.

Course, what I really like about Descent is the asymmetry of the two teams’ roles. The fact that playing as the forces of evil, spawning monsters and preparing traps, is a wildly different experience from being one hero in a party that’s expected to overcome any obstacle. Video games explore true asymmetry pitifully rarely, whereas take something like

Fury of Dracula.

This gem sees one player skulking around 19th century Europe as Count Dracula himself, while four other players slip into the riding boots of Lord Goldaming, Van Helsing, Wilhelmina Murray and Dr. John Seward, trying to hunt the ancient predator down before it’s too late.

It’s a brilliant experiment of predator and prey, with Dracula (who moves around the board invisibly) leaving a secret trail of the last six locations he visited, and four deadly hunters trying to close a net around him. The kicker is that actually arriving in the same location as Dracula can go either way. An aggressive Dracula versus an unprepared hunter might leave the hunter cripple, and Dracula only stronger.

DO YOU SEE HOW INTERESTING THIS IS? ITS PRETTY INTERESTING. PLAY THESE GAMES OR I WILL GO MENTAL.

LET’S TALK ABOUT AUCTIONS

Cyclades.

Auctions are an even simpler mechanic that board games revel in which video games studiously ignore. In life, everything has its price. So few video games ask you what that price is.

Cylades, which is a simple wargame that has players trying to build extravagant cities over a network of war-torn islands in ancient Greece, uses auctions excellently. At the start of every turn, players bid like wealthy drunkards for the affection of Ares, Poseidon, Athena and Zeus, with how many fat coins they actually have kept hidden behind a cardboard screen.

Only the player who wins Ares’ favour can train soldiers, move them, and construct forts. Poseidon’s the same, but for fleets and ports. Athena simply provides the philosophers required for actually building cities, while Zeus provides the priests and temples that boost your economy. Course, to do all of these actions once you have a god’s favour costs even more money.

This is as easy to grasp as it is a colossal mindfuck. Do you need Poseidon this turn? How much can you afford to pay? How much do you need your neighbour to not get Ares? And if you bid on Ares to drive the cost up, what are the odds that you’ll be stuck with him when no-one outbids you? Like I say, it’s clever. It also auto-balances the cost of powers which designers might otherwise have to playtest into space to determine their cost.

PRETTY GOOD HUH?

WHAT ELSE IS NEXT??!

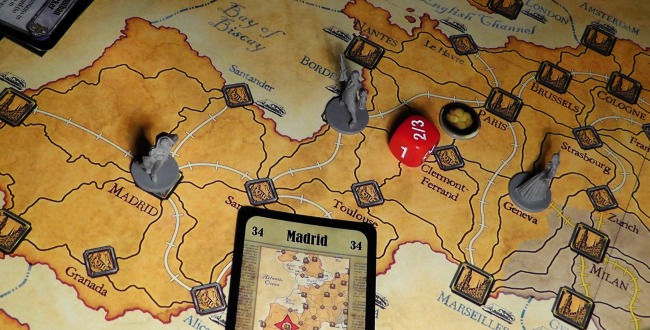

Risk Legacy.

I am sorry for my sass. I am. Still, at least board games are such an ancient medium that they see less of the kind of innovation that games have enjoyed since their inception.

Oh wait, no, that’s nonsense. At the moment, my friends are all playing Risk Legacy, a game that’s split the board gaming community like lightning striking a sapling.

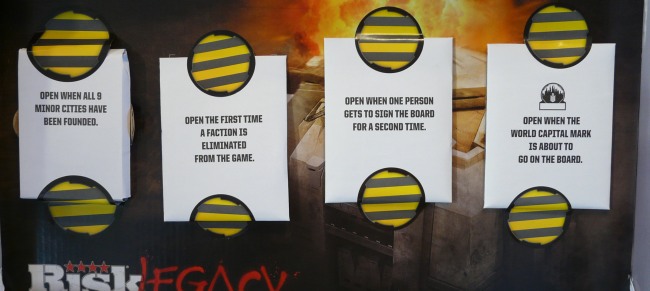

Risk Legacy sees players dueling for control of a far-future Planet Earth over the course of 15 games. Except, as the Earth changes in the face of centuries of war, so does the game. Everyone’s copy of Risk Legacy will evolve and devolve in unique ways as cards are torn up, the board is written on, stickers are slapped on it, and the rules of the game itself change. The box actually comes with sealed sections, their secretive contents only to be unleashed when certain conditions are met.

So, it’s a board game with spoilers. More than that, its competitors will build an actual history together, changing the face of the board itself as countries become fortified, irradiated, infested with cybernetic crabs… I mean, I’m guessing. I haven’t played it. But I’ve heard that it does hold some breathtaking surprises, and, more importantly, no-one can stop you from founding the city of Peter Blows or whatever.

This ties into the end of my last post where I said that a table game is just a shrink-wrapped idea. There’s a 1985 German board game called Waldschattenspiel where one of the players controls a tealight. Or look at this, or this, or this, or this. Innovation suffuses this hobby like a tea bag in the boiling water of play.

That analogy didn’t really work, did it?

Anyway, hopefully I’ve given you some food for thought.

We’re almost there now. Never mind all the crap I’ve talked about so far. In part 3 I’ll cover the real reason you should be playing board games. I’ll make a convert of you yet.

People have been asking what I’ve been doing recently.

WELL!

Call it video game detox. I’ve been pulling up fat handfuls of the roots of videogaming – board games, pen and paper roleplaying games, “live action” games – and chewing on them like some nerd herbivore.

While mobile gaming’s been continuing its frightening rise, I’ve been carrying 2 kilo board games to friends around London. While Mass Effect 3’s ending was shredded by gamers like so much pulled pork, I’ve been scribbling notes for my own 2300AD campaign. And while gamers are tapping their teeth in hesistant excitement for – what – Dishonoured? Bioshock Infinite? I’m trying to find the time to attend a Zombie LARP in an abandoned Redding shopping centre.

This isn’t me clawing at the jaws of a dinosaur as it goes bubbling down into a tar pit, either. Board game sales are actually increasing, year on year, and have been for more than a decade. Board games, would you believe it, seem to be coming back.

(Zombie LARP, by the way, is where you actually run away from actual guys pretending to be actual zombies, armed only with a pair of metaphorical balls and an actual Nerf gun.)

Now, in this post I’m not going to try and inspire you to take off your shirt and fling all your game consoles from the window. For that, we’d need you to visit my house, a crate of forty beers and a game of Memoir ’44: Overlord. In this post I just want to convey to you what’s exciting about analog game design itself.

Let’s start with me saying something nice and mad.

Technology, which is to say “digital” game design, is the single biggest obstacle game designers have ever faced.

The games industry is, in part, defined by a lust for new tech. Money has always found a home in a new console cycle, a new games platforms, a new graphics engine, a bigger game world, a more detailed game city, a more plausible AI, a new input device. These are all expectations sat on a AAA video game designer’s back before he’s typed the title of his design document.

But let’s take a step down, to the guys who are just working within existing formats rather than trying to push the envelope. There, technology still faces them with a horrific problem- if they can’t communicate their idea perfectly to the team of specialists required to turn that idea into a finished videogame, that idea is dead as sure as if it was suffocated by a beefy dude with some piano wire. If that doesn’t sound so hard, try writing the design document for Gears of War.

But let’s take yet another step down. Recently we’ve seen indie and mobile video games wandering into the spotlight with no make-up and no acceptance speech, having attained their success using only comparatively simple tech. Yet even in these cases the designer must still know how to code or how to transmit his vision to programmers, sound designers or whoever else. And if that doesn’t sound like much of a hurdle, let’s hypothesise that you had an amazing idea for a video game, but no programming experience. Imagine how far away that prototype would feel.

What we call “technology” is really a swimming pool so stuffed with sharks as to look like an undulating grey floor. It is this pool that ideas for video games must cross in order to exist. SNAP! goes a pair of jaws. The guns/punching/jumping in your game doesn’t feel satisfying. SNAP! The finished product is buggy. SNAP! You fail to assemble the finished project within the time or budget available to you. In a burst of foam and gore, your videogame is dragged down, down, through a gap in the shark mattress.

(Which is exactly why the “punk” movement within the indie scene is so exciting. Game designers using programs like GameMaker to make games with zero aesthetic appeal but a certain… heart, and purity of intent. Brendan Caldwell’s articles through that link kick ass, by the way. You should read them.)

But board games? With board games or card games, depending on how handy you are with a pair of scissors you can have a prototype up and running within hours. One of my favourite board games, Galaxy Trucker (which sees players racing to assemble spaceships in a 2D lego fashion before taking off in a heroic, rickety, doomed convoy), literally came to the designer in its entireity while he was taking a shower, and if he wanted to he could have been playtesting it the next day.

But we’re getting off track. The accessibility isn’t the point. The point is that this is lossless game design. There is no shark pit. When you buy a board game, what you take home and play is the original concept precisely as it was in the designer’s head. That’s the mecca for video games. For board games, it’s the norm.

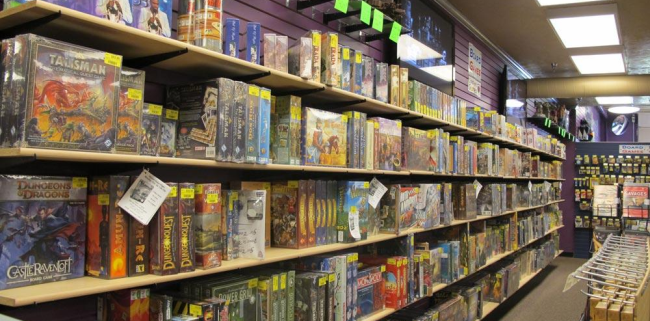

Let’s put it another way. You walk into a video game store and the shelves heave with fuck-ups, almosts, wannabes, disasterpieces, train wrecks, never-gonna-happens and shovelware. Your eyes drift to the charts, the sequels, the games you know, but the actual ratio of directionless embarrassments to successfully implemented visions is horrific.

You walk into a board game shop (not your Cranium or Cluedo, I’m talking proper nerd board games) and every one of the games on the shelves is a human being’s shrinkwrapped idea. There are still disasterpieces, licensed cash-ins and cynical sequels, but for the most part you can walk to any part of the shop, stare dead ahead and find yourself staring at the five lovingly playtested dreams of five human beings.

And they are dreams. The cross that the board gaming hobby has to bear is that there’s no money in it. No fucker plays these things. Depending on the publisher, a board game selling 20,000 copies might be seen as a happy success. But what this does mean is that most every designer is doing it for the love.

And that’s just the start.

COMING UP NEXT, I’ll start getting specific, pointing out a few board games that’ll show how this hobby is a minefield, except instead of mines you’re endlessly stepping ideas that are as surprising as mines, but usually more fun. Then in a third article I’ll talk about the REAL reason you should be playing board games. Until then, probably just have a browse of Shut Up & Sit Down, my board game review site. We’re doing the hobby justice, I think.